Korean War The Battle Begins for the Frozen Chosin

November 26, 1950 - The Chinese open the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir (right). Entering the Korean Conflict in October 1950, Communist Chinese for... View More

Be the first person to like this.

Be the first person like this

P61 Black Widow

Should McArthur have held at the Yalu River?

Throughout the nineteenth century, China's emperors had watched as foreigners encroached further and further upon their land. Time and again, foreigners forced China to make humiliating concessions. Foreign regiments, armed with modern weapons, consistently defeated entire imperial armies. Now, as a new century was about to begin, Tsu Hsi, empress dowager of the Ch'ing Dynasty, searched for a way to rid her empire of foreign parasites.

Austria, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Japan, and Russia all claimed exclusive trading rights to certain parts of China. They were dividing China into "spheres of influence." Some even claimed to own the territory within their spheres. By acquiring the Philippines, the United States became an Asian power too. Now, with a strong base of operations just 400 miles from China, American businesses hoped to take advantage of China's vast resources. The foreign spheres of influence, however, threatened their ambitions.

So while the empress was hoping to close China to foreigners, Americans were looking for a way in. John Hay, now Secretary of State, had an idea. Since public opinion, strained by the Philippines war, would never support the use of force, he decided to negotiate. He sent letters to all the foreign powers and suggested an "Open Door" policy in China. This policy would guarantee equal trading rights for all and prevent one nation from discriminating against another within its sphere. The nations replied that they liked the concept of the Open Door, but that they could not support or enforce it. Hay's plan had been politely rejected. Nevertheless Hay announced that since all of the powers had accepted the Open Door in principle, the United States considered their agreement "final and definitive."

While the outside powers bickered over who would control China, Tsu Hsi issued an imperial message to all the Chinese provinces.

The present situation is becoming daily more difficult. The various Powers cast upon us look of tiger-like voracity, hustling each other to be first to seize our innermost territories. . . . Should the strong enemies become aggressive and press us to consent to things we can never accept, we have no alternative but to rely upon the justice of our cause. . . . If our . . . hundreds of millions of inhabitants . . . would prove their loyalty to their emperor and love of their country, what is there to fear from any invader? Let us not think about making peace.

In northern Shandong province, a devastating drought was pushing people to the edge of starvation. Few people there were thinking about making peace. A secret society, known as the Fists of Righteous Harmony, attracted thousands of followers. Foreigners called members of this society "Boxers" because they practiced martial arts. The Boxers also believed that they had a magical power and that foreign bullets could not harm them. Millions of "spirit soldiers," they said, would soon rise from the dead and join their cause.

Their cause, at first, was to overthrow the imperial Ch'ing government and expel all "foreign devils" from China. The crafty empress, however, saw a way to use the Boxers. Through her ministers, she began to encourage the Boxers. Soon a new slogan -- "Support the Ch'ing; destroy the foreigner!" -- appeared upon the Boxers' banner.

In the early months of 1900, thousands of Boxers roamed the countryside. They attacked Christian missions, slaughtering foreign missionaries and Chinese converts. Then they moved toward the cities, attracting more and more followers as they came. Nervous foreign ministers insisted that the Chinese government stop the Boxers. From inside the Forbidden City, the empress told the diplomats that her troops would soon crush the "rebellion." Meanwhile, she did nothing as the Boxers entered the capital.

Foreign diplomats, their families, and staff lived in a compound just outside the Forbidden City's walls in the heart of Beijing. Working together, they threw up hasty defenses, and with a small force of military personnel, they faced the Boxer onslaught. One American described the scene as 20,000 Boxers advanced in a solid mass and carried standards of red and white cloth. Their yells were deafening, while the roar of gongs, drums and horns sounded like thunder. . . . They waved their swords and stamped on the ground with their feet. They wore red turbans, sashes, and garters over blue cloth. [When] they were only twenty yards from our gate, . . . three volleys from the rifles of our sailors left more than fifty dead upon the ground.

The Boxers fell back but soon returned. Surrounded, the foreigners could neither escape nor send for help. For almost two months, they withstood fierce attacks and bombardment. Things began to look hopeless. Seventy-six defenders lay dead, and many more were wounded. Ammunition, food, and medical supplies were almost gone. Then, shortly before dawn, loud explosions rocked the city. Weary defenders staggered to the barricades, expecting a final, overpowering Boxer attack. But as a column of armed men approached them, they began to cheer. Help had arrived at last.

After a month of no news from their diplomats, the foreign powers had grown worried. They assembled an international relief force of soldiers and sailors from eight countries. The United States, eager to rescue its ministers and to assert its presence in China, sent a contingent of 2,500 sailors and marines. After rescuing another besieged delegation in Tientsin, the international force marched to Beijing, fighting Boxers and imperial soldiers along the way.

The international troops looted the capital and even ransacked the Forbidden City. Disguised as a peasant, the empress dowager escaped the city in a cart. She returned to the Forbidden City a year later, but the power of the Ch'ing dynasty was destroyed forever.

Because it had participated in the campaign, the United States participated in the settlement that followed. Hay called for an expanded "Open Door," not only within the spheres of influence, but in all parts of China. He also recommended that the powers preserve China's territory and its government. Other powers agreed, and the Open Door policy allowed foreign access to China's market until World War II closed it once again.

Be the first person to like this.

Be the first person like this

P61 Black Widow Heston & Niven played great parts in that film, as well as John Ireland.

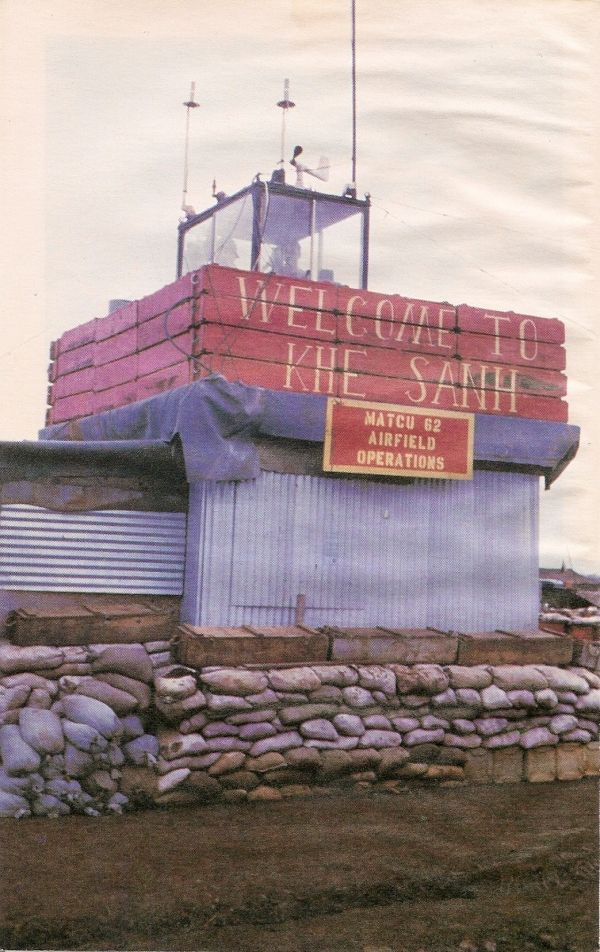

The Khe Sanh Siege

On January 21, 1968, North Vietnamese forces surrounded U.S. Marines at Khe Sanh in 1968, beginning a 77-day siege that became one of the Vietnam War’s most controversial battles.

... View More

1 person likes this.

, P61 Black Widow reacted this

1807 Aaron Burr was arrested for alleged treason

Aaron Burr, a former U.S. vice president, is arrested in Alabama on charges of plotting to annex Spanish territory in Louisiana and Mexico to be used ... View More

Be the first person to like this.

Be the first person like this

The Riddle of Edgar Allan Poe’s Death

The famed writer died suddenly—and under strange circumstances.

Despite his macabre literary genius, Edgar Allan Poe’s life was short and largely unhappy. After... View More

Be the first person to like this.

Be the first person like this