An October 1775 Birthday for the Continental Navy

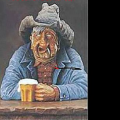

Unity vs. Margaretta, 12 June 1775 by Robert Lambdin (Naval History and Heritage Command). Margaretta was a Royal Navy vessel captured off Machias, then part of Massachusetts, but now in Maine. The image illustrates the relatively small sizes of vessels involved in creating the early American navy.

During the first six months of the American rebellion, the colonies inched toward some means of dealing with Britain’s naval superiority. Over the summer, the Americans had already waged a sort of whaleboat war among the estuaries and islands around Boston, mainly to deprive the British army couped up there of forage and fodder. Efforts escalated as the war continued. A confrontation between small Royal Navy vessels and the Massachusetts town of Machias over the summer serendipitously resulted in a small Massachusetts Navy created by capture in June 1775.[1] In June, Rhode Island’s General Assembly voted to charter two ships and outfit them for naval operations to protect the colony’s trade, essentially by contesting the Royal Navy’s control of Narragansett Bay.[2] In September, Colonel John Glover in the Continental Army offered his fishing schooner, Hannah, as a charter to wage war on the sea. George Washington naturally accepted, limiting its operations to capturing unarmed supply ships serving the British army.[3] The army had essentially created its own navy out of necessity.

The explicit question of coordinating continental naval power fell to the Continental Congress on Tuesday, October 3, when a delegate from Rhode Island, announced his colony’s conclusion that “the building and equipping of an American fleet, as soon as possible, would greatly and essentially conduce to the preservation of the lives, liberty and property of the good people of these Colonies and therefore instruct their delegates to use their whole influence at the ensuing congress for building at the Continental expence a fleet of sufficient force for the protection of these colonies, and for employing them in such a manner and places as will most effectually annoy our enemies, and contribute to the common defense of these colonies.”[4] At the time, Congress was preoccupied with governing colonial trade, both internal and external, so it decided to put off consideration of Rhode Island’s proposal until “Friday next.” (The primary trade question was how to implement the non-importation and exportation agreements, how the costs of non-exports would be spread across society, and how the agreements might be loosened to facilitate the importation of gunpowder, arms, and munitions.)

The Congress kept discussing trade issues throughout the week without resolving much. But, naval matters kept intruding. On Thursday, Congress received and reviewed a packet of letters from London, one of which included the news that two vessels had departed England carrying munitions to Canada.[5] It quickly appointed a committee of three men to determine a course of action—John Langdon of New Hampshire, Silas Deane of Connecticut, and John Adams of Massachusetts. New Englanders all, they were already on record supporting moves to create a Continental Navy.[6]

Surprisingly, there was some opposition to creating the committee in the first place. Historiography on the debate is, unfortunately, vague. The Journals of the Continental Congress themselves do not rehash debates, unsurprising since they focus almost entirely on actions, motions made, and resolutions agreed to. Instead, they tell us that a committee was appointed, its report considered, and the actions Congress took as a result. The substance of the report or any controversy it sparked are left unspoken. Historians instead turn to John Adams and his notes on the positions taken by various delegates.[7] Their original publication in the American Archives indicated the debate over a navy took place during consideration of the committee intended to develop courses of action for dealing with the two Canada-bound British cargo vessels, suggesting debate over the committee served as a surrogate for wider debate over the creation of a navy.

According to Adams, Samuel Chase of Maryland thought, “It is the maddest idea in the world to think of building an American fleet…we should mortgage the whole Continent.”[8] Georgia’s John Zubly, not yet willing to consider separation from Britain, agreed that an American fleet would be extravagant, but conceded it would be necessary if the plans of “some gentlemen were to take place.” Presumably, he was referring to the more aggressively minded rebels like John and Sam Adams, who had already expressed their sentiments about independence in private. Silas Deane, who had shared his support for a navy of some sort with John Adams, desired a serious debate on the creation of a navy. Although Christopher Gadsden of South Carolina held similar sentiments, he opposed Rhode Island’s proposal as overly ambitious and argued for studying the problem before committing to a course of action. He was joined by fellow South Carolinian John Rutledge, who proposed forming a committee to study the larger problem of naval power and declined expressing an opinion about a navy until there was a formal structure he could consider. Zubly proposed leaving it to Rhode Island to propose something more specific, that colony having taken the lead on the matter. John Adams, perhaps recognizing that the debate’s momentum was moving in the wrong direction, attempted to bring things back to the topic at hand: a decision about how to react to the reports of two British cargo vessels carrying arms and munitions to Canada. With that, Congress decided against appointing a committee to develop a comprehensive proposal for a navy, instead moving on to appoint a committee on intercepting the cargo vessels.[9]

That committee quickly reported out, and Congress adopted a resolution to recommend to General George Washington that he request Massachusetts to place its tiny new navy under the general’s command for the purpose of intercepting British cargo ships and, similarly, that Rhode Island and Connecticut would be directed to do the same. In short, the Continental Congress put off Rhode Island’s recommendation to build a Continental Navy and instead ordered Washington to co-opt colony navies for the purposes of intercepting unarmed British shipping.[10] As President of the Congress, John Hancock quickly passed on the guidance to Washington, clarifying that the master, officers, and seamen crewing such ships would be entitled to prize money and that the Congress would pay for their service and indemnify ship owners against the financial risks.[11] It was a compromise.

The question of creating a continental navy would not die, however. Congress began on Friday, October 13, with further discussions on trade. That inexhaustible subject came to a brief halt when Washington’s response to Hancock’s letter of October 5 arrived and updated the Congress on how he was implementing his instructions. The Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army confessed that he had already armed some ships for the very purposes of intercepting British cargo vessels—this was a reference to Hannah—and was in the process of outfitting more when Hancock’s letter arrived in Cambridge. (Washington’s letter was dated October 12 and arrived in Congressional hands the next day; it is not clear why it took a week for Hancock’s October 5 letter to arrive in Cambridge and prompt a reply.) Washington also updated Congress that ships from Connecticut and Rhode Island were unavailable, but that he would make every effort to follow Congressional guidance with those ships he was acquiring for the Continental Army.[12] In a separate letter to his brother John, Washington referred to these vessels as “privateers,” which, strictly speaking, they were not.[13] Although they might be leased, they were taken into Continental Army service and crewed by army officers and soldiers. While prize money would be available to the officers and crew for any cargo they captured, the Continental Army had essentially indemnified ship owners against risk should the vessels be lost.

General Washington’s actions prompted Congress to revisit the question of a continental navy, since the army commander-in-chief had, in effect, already created one. The earlier attempt to leave the burden of a navy to individual colonies was effectively rendered moot by Washington’s actions. So, the Congress returned to the committee report crafted earlier by Langdon, Deane, and Adams. After some debate, it resolved “That a swift sailing vessel, to carry ten carriage guns, and a proportionable number of swivels, with eighty men, be fitted with all possible dispatch, for a cruise of three months, and that the commander be instructed to cruise eastward, for intercepting such transports as may be laden with warlike stores and other supplies for our enemies, and for such other purposes as the Congress shall direct.” Then it resolved to appoint a committee of three men to prepare an estimate of the expense and “lay the same before Congress, and to contract with proper persons to fit out the vessel.”[14] The grammatical construction of the resolution is odd, since it appears to decide to outfit a ship before determining the cost, which would be reported to Congress as the committee entered into contracts to fit out the ship. The resolution became odder still when in the very next sentence, it resolved to fit out a second, identical ship, while also receiving a report from the aforementioned committee about the proper kind of vessel to acquire and an estimate of the expense. The language bears all the hallmarks of a compromise being developed in real time as the resolution was recorded. In any event, this was not strictly an ex post facto endorsement of the actions Washington had already undertaken. First, the mission was broader than the earlier focus on two cargo ships bound for Canada. Second, these two new vessels would be directed by Congress, not George Washington and the Continental Army. Third, by creating a new committee, Congress would undertake the outfitting of the ships itself, again not deferring to Washington. (Langdon and Deane again were appointed to this new committee, but Southernor Christopher Gadsden replaced John Adams.)

Thus, the Continental Navy was born on October 13, 1775.

[1] Nathan Miller, Sea of Glory: A Naval History of the American Revolution (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1974), 30-35.

[2] https://emergingrevolutionarywar.org/2025/06/05/captain-james-wallaces-tumultuous-june-1775-in-narragansett-bay/

[3] “George Washington’s Instructions to Captain Nicholson Broughton, 2 Sept. 1775,” in William Bell Clark, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution, Volume I, 1287-1289. Hereafter NDAR, Volume, Page; William M. Fowler, Jr., Rebels Under Sail: The American Navy during the Revolution (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1976), 28-29.

[4] Library of Congress, Journals of the Continental Congress 1774-1789, September 21 – December 30, 1775, Volume III (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1905), 274; Tim McGrath, Give Me a Fast Ship: The Continental Navy and America’s Revolution at Sea (New York: NAL Caliber, 2014), 16-17; Miller, Sea of Glory, 41. The Journals of the Continental Congress themselves are silent on who raised Rhode Island’s instructions to its delegates. McGrath believes it was Hopkins. Miller thought it might be Samuel Ward. Hopkins was a leading proponent of a navy and engaged in the debate that ensued, so we can speculate that he the more likely candidate.

[5] Journals of the Continental Congress 1774-1789, III, 278.

[6] Journals of the Continental Congress 1774-1789, III, 277, note 1.

[7] Miller, Sea of Glory, 43; McGrath, Give Me a Fast Ship, 18-19.

[8] The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States, Vo. II (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1850), 463. These are Adams’ words as no verbatim transcript of the debate exists.

[9] Ibid; Journals of the Continental Congress 1774-1789, III, 278. Historians generally tie Adams’ notes on the naval debate to discussions on October 5 about intercepting the Canada-bound cargo ships and the original October 3 Rhode Island proposal to create a navy. However, Adams’ notes make more sense in the context of a subsequent debate on October 13 that actually resulted in creation of a two-ship navy. The October 13 resolution more closely tracked with the topics Adams described in the debate, whereas the substance of the debate veered considerably away from the immediate task and resolutions before Congress on October 5. To complicate matters further, Charles Francis Adams, John’s grandson, who compiled and edited the work, placed the debate on Saturday, October 7, after Congress had already resolved to rely on Massachusetts and Rhode Island to intercept the cargo ships and Hancock had communicated Congressional guidance to Washington. In all likelihood, Adams’ notes should not be read as a real time debate, but as his effort to capture the positions of various delegate over time when naval issues were discussed on several occasions that October.

[10] Journals of the Continental Congress 1774-1789, III, 279.

[11] “John Hancock to George Washington, 5 October 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0099.

[12] “George Washington to John Hancock, Octr 12th 1775,” NDAR, II, 415. Washington’s inquiries to Connecticut and Rhode Island may explain the delay in his response to Hancock’s October 4 letter.

[13] “George Washington to John Augustine Washington October 13, 1775,” NDAR, II, 436.

[14] Journals of the Continental Congress 1774-1789, III, 293.

Dimension:

1200 x 782

File Size:

94.03 Kb

1 person likes this.

, P61 Black Widow reacted this

P61 Black Widow

Great history